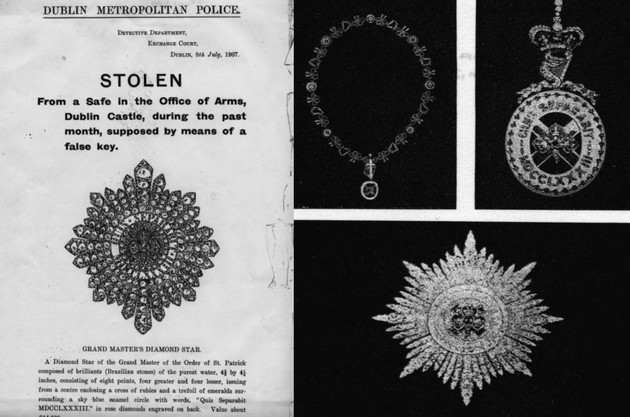

In 1907, in what remains one of the great unsolved jewel thefts, the Irish Crown Jewels were stolen from inside Dublin Castle. None of them have ever been recovered, and no one was ever arrested for the theft. It was one of the mass media sensations of its day, in Ireland and beyond – the combination of spectacular royal jewels, an apparently perfect crime, and rampant speculation about the possible involvement of senior figures of the Irish and English establishment meant that it received enormous press coverage, resulting in at least one libel case as a result of over-enthusiastic theorising about the culprits.

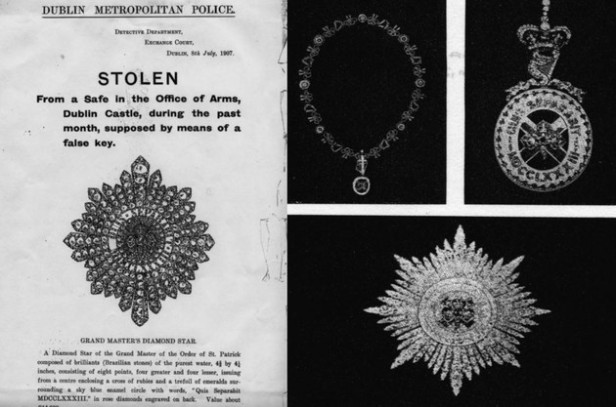

The jewels themselves consisted of two star and badge regalia of the Order of St Patrick (one of which was reserved for the Sovereign) and five collars belonging to Knights of the Order. They were large pieces of ceremonial jewellery, consisting of diamonds, emeralds and rubies, and were collectively valued at more than £30,000 (well over £3m today). They were kept in a safe inside the office of Arthur Vicars, the Ulster King of Arms and therefore a senior government official at Dublin Castle. The jewels’ disappearance was discovered just 4 days before the arrival of Edward VII and Queen Alexandra for the Irish International Exhibition, and prompted enormous royal embarrassment, an official commission of enquiry and by 1912 had become the subject of acrimonious exchanges in the Westminster parliament when it was alleged (under cover of parliamentary privilege) that the solution to the theft had been covered up by authorities because it was connected to “criminal debauchery and sodomy being committed in the castle by officials, Army officers…of such position that their conviction and exposure would have led to an upheaval from which the Chief Secretary shrank”. Over the century since the theft, accusations have been made against individuals including the Lord Lieutenant’s son Lord Haddo, and the explorer Ernest Shackleton’s brother Francis as well as Vicars himself (like Vicars, Shackleton was employed in the Castle and had access to the safe from which the jewels disappeared). It has been described variously as a conservative plot to discredit and embarrass the Liberal government (represented in Dublin Castle by Lord Aberdeen, the Lord Lieutenant) and as an IRA plot to embarrass the entire British administration and raise funds by selling the jewels in America. While it seems most likely the jewels were smuggled abroad immediately to be broken up and sold, as late as 1927 some official Irish sources appeared to believe they were still extant and available for sale on the black market, whereas yet another version of the story suggests that the British royal family secretly bought them back not long after they were stolen, again in order to hush up a homosexuality scandal most likely involving Francis Shackleton and another Castle official with access to the jewels. Neither they nor anyone else was ever arrested or charged with the crime, although Shackleton was imprisoned and disgraced some years later for another theft. After dominating newspaper stories in Ireland and England in 1907, the story has continued to reappear every few years for more than a century, whenever a new theory emerges as to the culprits or the jewels’ fate. My personal favourite can be found here, but a cursory search will produce many more, and there have also been fictional versions (including a very salacious novel called Jewels, published in 1977) and a 2003 television documentary.

It may even have attracted the attention of Sherlock Holmes, as it has been suggested that Conan Doyle’s story ‘The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans’ (published in December 1908) was inspired by the theft of the Irish crown jewels, an argument that is certainly plausible. While no details of the story reflect the case, its basic structure (the theft and smuggling abroad of top secret military plans from a government safe, which turns out to have been the work of a trusted establishment figure) is similar in its main points. It is beyond the scope or expertise of this blog to adjudicate on whether the case was an influence on Conan Doyle, though the timing of the story’s publication eighteen months after the jewels’ disappearance does add credibility to the idea. What is certain however, is that the theft’s resemblance to a Sherlock Holmes story was clear to others at the time. In March 1908, a story entitled ‘Sherlock Holmes in Ireland, or The Diamonds of St Patrick. From the French’ had appeared in the story paper Ireland’s Own. The faithful Dr Watson who narrated most Holmes stories was here abandoned in favour of an unnamed French narrator, who nevertheless recounts the tale in the typical first person style of other Sherlock cases. According to this (very) short story, Holmes was asked to investigate the jewels’ disappearance, prompting his first visit to Ireland, of which the narrator comments, “he resembled in that nine-tenths of the English, who are keen travellers, but Ireland, poor and unhappy Ireland, in place of attracting them, repulses them. Without doubt they feel themselves culpable in this place, and they fear to see the pleasures of travelling spoiled by their regrets”. Having arrived in Dublin, Holmes and his narrator attend a levee at Dublin Castle, which provokes some republican disapproval from the French narrator, who is proud to describe himself as a ‘citizen of a Republic’. The plot then follows (extremely rapidly) a series of fairly standard Holmes detection techniques, including Holmes faking a faint outside the strong-room from which the jewels were stolen in order to be carried inside to inspect it, and then appearing in not one but two apparently convincing disguises (as both a country squire and a plumber). Finally he announces to the narrator that he knows who stole the jewels – but when asked to name the culprit, he responds “Wait until tomorrow evening…There is a great ball at the Viceroy’s Castle. At the particular moment when Lord Aberdeen, accompanied by his court, shall make his entry into the hall…I shall unmask the robber”. However, the next evening Holmes shows the narrator a telegram he has just received from some unnamed but senior member of government, begging him not to reveal the thief’s identity ‘for the safety of your country’. Holmes complies, explaining “I strongly suspect that there is underneath some affair of the State. If I made public my inquiry terrible calamities would happen. Perhaps we would have war with Germany”. And there the story ends, Holmes and our mysterious French narrator returning to London and the jewels remaining lost.

The story is thin, especially by the standards of Conan Doyle’s own prose, but its invention was in itself very clever – the theft of the Irish crown jewels from inside Dublin Castle, the failure to recover them, and the rumours and accusations swirling around several suspects who would normally have been considered above suspicion was itself highly reminiscent of a Sherlock Holmes case, and whoever wrote the story had obviously understood this very well. The story’s resolution of Holmes knowing the culprit’s identity but withholding it at the request of a very senior member of the establishment in order to protect matters of State also sailed tantalisingly close to some of the rumours about the theft which would have been widely-known in Ireland by the end of 1908, while remaining vague enough to avoid charges of libel from the individuals concerned. Of course, by 1912 some of those rumours would be publically stated in Parliament, but those statements had the benefit of parliamentary privilege, which Ireland’s Own did not.

But to modern readers, perhaps the most remarkable feature of this story was not its avoidance of libel accusations, but instead its cheerful breach of copyright law. In 1908, Arthur Conan Doyle was one of the best-selling writers in the world, and Sherlock Holmes was so popular that Doyle had famously had to bring him back from the dead in 1903. The stories had always been serialised in the Strand magazine, for whom they had been exceptionally lucrative, and were then collected in book form which also sold in enormous numbers. The publishing of a story using Holmes’ name, persona and distinctive detecting style was therefore an obvious attempt to take advantage of readers’ enthusiasm for Conan Doyle’s work – and was blatantly illegal. International enforcement of copyright claims such as this was still difficult, if not quite as impossible as it had been for most of the 19thC, when for example the American publishing industry had been largely founded on the wholesale pirating of English material. But Ireland and England operated under effectively the same copyright regimes in 1908, and had Conan Doyle or his publishers been aware of ‘Sherlock Holmes in Ireland, or The Diamonds of St Patrick’, they would have been in an unquestionable position to sue Ireland’s Own and its publisher, John Walsh. Given that Walsh ran the story paper so successfully – and indeed owned several newspapers and a large printing works – it is inconceivable that he and his staff did not know that their ‘Sherlock Holmes’ story was an actionable breach of copyright. By contrast, it is not entirely certain that the Ireland’s Own readership (many of whom were barely out of school) would all have understood that the story wasn’t actually by Conan Doyle, a point which would surely have enraged the author all the more had he ever known of it. The story’s publication is therefore an indication that the editorial staff of Ireland’s Own felt secure that it would not be seen by anyone with a professional interest in the authentic Sherlock Holmes stories – a sign perhaps that despite their occasional attempts to promote sales among Irish emigrants in Britain, in reality the paper did not circulate significantly outside Ireland. This appears to have been an accurate prediction on their part, as the story seems to have generated no legal action – and remains the occasion of Sherlock Holmes’ only visit to Ireland. And the Irish crown jewels remain missing.

References

The Theft of the Irish ‘Crown Jewels’ Online Exhibition 2007, National Archives of Ireland http://www.nationalarchives.ie/digital-resources/online-exhibitions/the-theft-of-the-irish-%E2%80%9Ccrown-jewels%E2%80%9D-2007/

Arthur Conan Doyle, ‘The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans’, His Last Bow and the Casebook of Sherlock Holmes (Penguin Classics, 2008).

Robert Perrin, Jewels (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1977)

The Strange Case of the Irish Crown Jewels (dir. Gerry Nelson, 2003)