Advertising & Products, Cultural History, Radio

The Irish Free State and the Radio Age

Cultural History, Newspapers & Magazines, Radio

The Media Landscape of the Irish Free State

As I Was Saying…

Advertising & Products, Fiction, Newspapers & Magazines

The long life and after-life of ‘Mick McQuaid’

Cultural History, Newspapers & Magazines

Mass media, High Society and the invention of Celebrity

Books & Pamphlets, Fiction, Newspapers & Magazines

The Catholic Truth Society of Ireland: Making Morality Pay

Books & Pamphlets, Cultural History, Newspapers & Magazines

Deserters and White Slavers: Emigration in the Irish popular press

Fiction, News & Current Affairs, Newspapers & Magazines

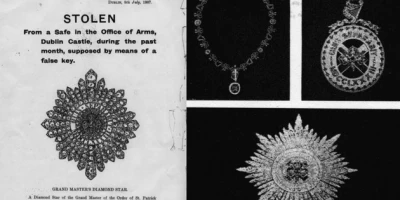

The Curious Case of Sherlock Holmes and the Irish Crown Jewels (or not)

Advertising & Products, Newspapers & Magazines, Shops & Businesses