The ‘Why Go Bald’ sign on South Great George’s Street in Dublin is one of the city’s most-loved landmarks. One of the few remaining examples of neon advertising, it consists of a man’s head and shoulders, in which as the lights flash on and off he alternates between a full head of hair with a big smile, and total baldness with a frown. Designed in 1962 for the hair restoration clinic which still operates underneath it today, it is an icon of design history and also a reminder that our own era’s obsessions and anxieties about hair as an indicator of youthfulness and vitality are nothing new. In fact, advertisements for hair restorers, hair dyes, hair ‘food’ and even hair removal techniques were among the most frequent and visible examples of modern advertising, from the end of the 19thC.

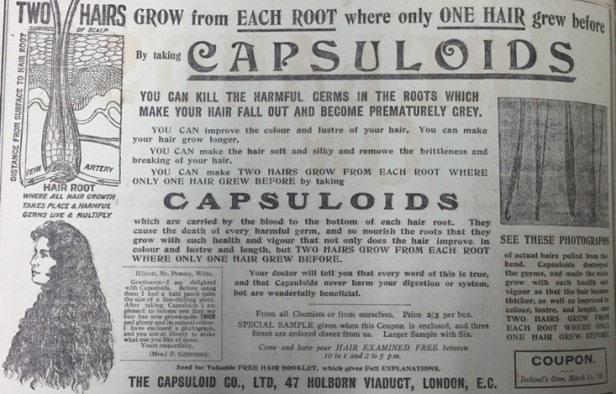

Hair products were a very distinct sub-group of heavily-branded ‘personal grooming’ products, and the range and frequency with which they were advertised was striking. It is also noticeable that although some products simply claimed to clean, style or perfume hair, far more were focused upon eliminating the twin horrors of baldness and greying. Where baldness was concerned this was where, in an era of almost unregulated advertising, hair products intersected with quack medicine. A range of ‘hair restorers’ promised men (and sometimes women) that their thinning hair would be revived and grow like new. This was often accompanied by pseudo-scientific claims to have discovered the cause of thinning hair, and found a solution to it. Capsuloids, for example, claimed that hair loss was caused by ‘harmful germs’ in the hair roots – their product would not only kill these germs, but ‘…so nourish the hair roots that two hairs will grow from each root where only one hair grew before’. Their adverts often included a diagram of the scalp and hair root drawn at dramatic magnification, in order to demonstrate exactly where the harmful germs were lurking prior to taking Capsuloids. By contrast, their competitor Harlene Hair Drill claimed to have made an ‘Appalling Discovery Which Affects Your Hair. National Danger of Baldness’. Rather than germs, Harlene identified ‘scurf’ as the cause of hair loss, sternly warning that ‘no hair can withstand the insidious attacks of this loathsome scurf’ and illustrating the point with ‘before’ and ‘after’ drawings of baldness cured. In other adverts Harlene, obviously keen to let no hair restoration possibilities pass them by, also promised that their product was ‘unequalled for promoting the growth of the Beard and Moustache’, and even ‘Curing Weak and Thin Eyelashes’. Capsuloids and Harlene were advertised with British addresses for the placing of postal orders, but some enterprising Irish firms produced their own products, such as Boyd’s Oriental Hair Restorer, which also claimed that it would prevent baldness by curing dandruff, and could be purchased from their premises in Mary Street, Dublin.

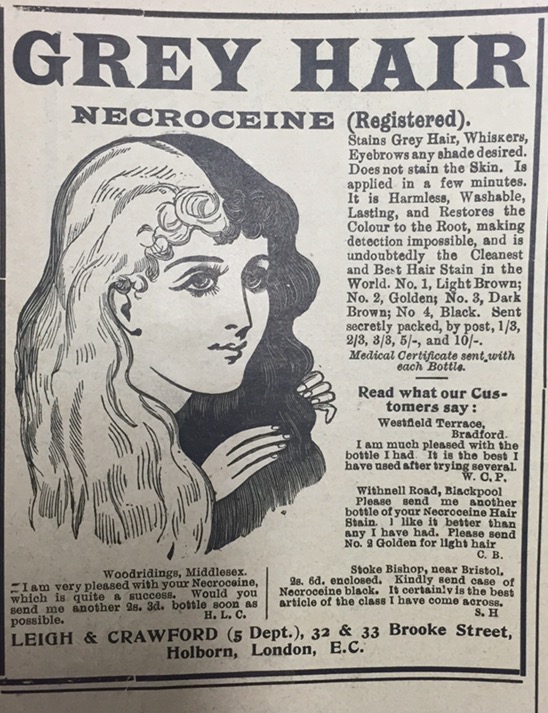

If hair loss was perhaps the greatest concern to be exploited by the purveyors of patent cures, then going grey came a close second. If the adverts in papers and magazines are any indicator, both the men and women of early 20thC Ireland were routinely dying their hair, presumably with varying degrees of skill and subtlety. In 1911 the front wrapper of an issue of Ireland’s Own contained no fewer than 4 separate advertisements for pharmacies selling hair dye. These included J Leonard & Co on North Earl Street Dublin, who assured readers that ‘There Is No Need to Look Old’ and JJ Fitzgibbon of Kingstown who chose the more imperative ‘Don’t Look Old’. The alarmingly-named Necroceine hair dye made the highly unlikely claim in its advert that it ‘restores colour to the root, making detection impossible’.

If the loss of hair or hair colour was one age-related anxiety to be addressed through patent cures, then the appearance of hair in the wrong places was another. By the start of the 20thC, there were plenty of electrolysis practitioners advertising their services in Ireland – and here perhaps we might pause to contemplate just how painful and downright dangerous early 20thC electrolysis probably was – to those keen to remove ‘unsightly hair’.

Mrs Pomeroy, who had a beauty salon on Grafton Street and sold her own range of ‘skin foods’, offered it, as did the city’s most upmarket hair salon, Maison Prost on St Stephen’s Green (which sometimes advertised itself as being ‘coiffeur, parfumeur, etc to his Excellency the Lord Lieutenant’, and remained in business until the 1960s). Alternatively Miss Hulbert of Ballsbridge regularly advertised her electrolysis service, and Miss Read of Dawson Street offered electrolysis and facial massage. Most alarmingly of all, in 1907 readers of Irish Society were invited to purchase a ‘Tensfeldt Apparatus’ in order to perform electrolysis on themselves in the privacy of their own homes. Amazingly, no accounts of fatalities appear to have been recorded!

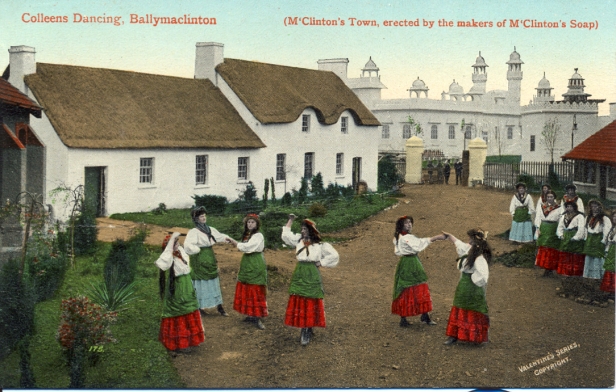

As was discussed here in an earlier post, the development of branded products (of which hair restorers and dyes were examples) led not only to an increase in the quantity of advertising in order to embed the brand in customers’ memories, but also to a more important shift in tone of that advertising. The move was from an ‘informative’ tone which emphasised the availability and nature of products customers were already looking for, towards an ‘emotive’ tone which sought to create markets for products customers did not yet know they wanted by highlighting a need or problem which only that brand could solve. Inevitably this change of tone meant that advertising increasingly played upon people’s fears and anxieties (‘psychoanalysis in reverse’, as Leo Lowenthal would famously describe the profession in the mid-20thC). It was therefore no coincidence that products promising to make people look younger and better-looking were those suited to this new style of advertising, and upon which the modern advertising industry was built. Aggressively branded, with wildly imaginative names and logos, their advertisements developed some of the first uses of an appeal to emotions, aspirations and fears in order to convince customers that their product – and only their product – could make them happier, healthier and more successful. This had an obvious logic to it – it is not particularly difficult to invoke fear and anxiety in most people regarding their health, youthfulness and physical attractiveness, and this is why products such as soaps, quack medicines and beauty products were those which pioneered this approach to marketing. Soap advertising is often credited with effectively pioneering the principles and techniques of modern advertising, and with good reason. A product easily mass-manufactured cheaply and on an industrial scale, and also one which was small, simple to package, transport and sell cheaply, it was an obvious vehicle for mass advertising and in Ireland as elsewhere the pages of every newspaper and magazine were dominated by soap adverts by the end of the 19thC. Not only were these often lavish, full-colour illustrations such as the famous use by Pears Soap of Millais’ painting ‘Bubbles’, but they were also pioneers of brand-names, advertising slogans and images which sought to play on the emotional possibilities of their product – promising sunshine (‘Sunlight’ soap), brightness and health versus grime and disease without them. In a world which still had high levels of infant mortality, medical care of limited effectiveness, and few of the labour-saving devices we consider necessary to clean our homes, our clothes or ourselves, people had good reason to fear dirt and disease and advertisers rapidly learned to prey upon those anxieties. While the international brands such as Sunlight and Lux were the dominant advertisers, an Irish brand called McClinton’s soap (manufactured in Donaghmore, Co Tyrone) achieved considerable success as a luxury brand which was heavily (and inventively) advertised using a fake Irish village called Ballymaclinton, and images of Irish ‘colleens’ whose soft complexion was attributed to their use of McClinton’s soap.

Then as now advertisements were often a revealing indicator of the anxieties of a particular cultural moment. The frequency of advertisements for hair restorers and dyes – and the fact that they appeared across an enormous range of Irish publications – suggested that what all of these potions, tablets and treatments had in common was their ability to prey upon the anxieties of a population keen to appear young and vigorous. The prices, style of adverts and range of publications they appeared in demonstrate that this quest for youthfulness crossed class, gender and other demographic lines. While electrolysis was only advertised in the upmarket publications (and offered at upmarket salons such as Maison Prost) and was presumably an expensive treatment, most of these brands were cheap, a shilling or less per bottle, so apparently fears about personal appearance (and aging) were pretty much universal across otherwise significant divides of class, gender and location. The cult of youth we often associate with post-World War One (with its flappers, jazz babies and dramatically more adolescent-looking beauty ideals for women) had actually begun to manifest itself much earlier. The ‘new woman’ who became the subject of so much discussion and agonising from 1890 onwards took various forms, but perhaps most frequently was a very young woman who challenged social conventions about work, dress and relationships as she first reached adulthood. In America this emphasis upon female youthfulness was particularly evident in the early 20thC fascination with that beguiling creature the college ‘co-ed’, often depicted in the style of the famously vigorous ‘Gibson girls’. While Ireland did not share the ‘co-ed’ phenomenon, its leading women’s magazine, Lady of the House, did make reference to changing conventions of female beauty in 1907 by citing the ‘Gibson ideal’, suggesting that it was an internationally-understood concept by that point. Less light-heartedly, a widely-pervading sense of anxiety about being ‘left behind’ was clearly evident in the wider culture of the early 20thC, in a society increasingly framed by a sense of competition. For women, this took the form of concerns about being left ‘on the shelf’, as the popular press frequently stoked fears about the declining marriage rate, alternatively blaming ‘new women’ for being poor wife material, or blaming men for not wanting to take on the responsibilities of marriage – at one point the Irish Packet even discussed a proposal (made in all seriousness) for a ‘bachelor tax’ to resolve this problem. Either way, in a world in which marriage was still the primary ambition for most women for both cultural and pragmatic reasons, the fear of being an ‘old maid’ overtaken by younger competitors on the marriage market was real. For men, the fear was of being thrown ‘on the scrap heap’, especially for working-class or lower-middle-class men at the mercy of employers who could almost always find a younger and cheaper replacement. Those doing manual labour had an obvious incentive to wish to appear young and strong, but the rapidly-expanding army of clerks and other low-ranking office workers also had reasons for anxiety about being seen as over-the-hill and expendable. The combined effects of these all of these cultural currents then, was a market of both men and women apprehensive about visible signs of aging – and therefore receptive to the promise that their youthfulness could be regained for the price of a shilling bottle of hair restorer.

References

Stephanie Rains, ‘“Do You Ring? Or Are you Rung for?”: Mass Media, Class, and Social Aspiration in Edwardian Ireland’, in New Hibernia Review, 18/4 Winter, 2014.

Stephanie Rains, ‘The Ideal Home (Rule) Exhibition: Ballymaclinton and the 1908 Franco-British Exhibition’, in Field Day Review 7, 2011.

Juliann Sivulka, Stronger Than Dirt: A Cultural History of Advertising Personal Hygiene in America, 1875-1940, Prometheus Books: New York, 2001.