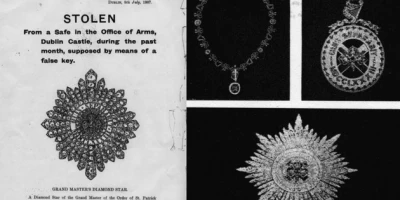

Books & Pamphlets, Cultural History, Newspapers & Magazines

6 Posts

Books & Pamphlets, Cultural History, Newspapers & Magazines

Fiction, News & Current Affairs, Newspapers & Magazines

Books & Pamphlets, Cultural History, Newspapers & Magazines

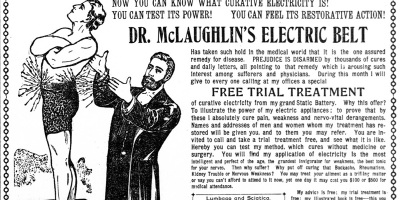

Advertising & Products, Fiction, Newspapers & Magazines

Cultural History, Fiction, Newspapers & Magazines

Cultural History, Fiction, Newspapers & Magazines