Earlier this month it was noted in some newspapers that the only religious education textbooks approved by the Catholic Church for use in the primary schools they control (which is 90% of public primary schools in the country) are published by the Church’s own publishing house, Veritas. This was felt to be particularly worthy of comment because those textbooks are believed to be the only profitable part of Veritas’ business these days, and therefore very important to its survival. This is a far cry from its hey-day in the mid-20thC, or even its early-20thC origins in the Catholic Truth Society.

The Catholic Truth Society of Ireland was established in 1899 (an English equivalent had been founded a few years earlier) with the intention of ‘the diffusion, by means of cheap publications, of sound Catholic literature in popular form, so as to give instruction and edification in a manner most likely to interest and attract the general reader’, as explained by its first President, the Bishop of Clonfert an address to members that year. In terms very recognisable to anyone familiar with the social purity movement of the era, the Bishop went on to assert that ‘It is well known that various printing presses in Great Britain daily pour out a flood of infidel and immoral publications, some of which overflows to this country. We have a confident hope that the Society’s publications will remove the temptation of having recourse to such filthy garbage, will create a taste for a pure and wholesome literature, and will also serve as an antidote against the poison of dangerous or immoral writings’. As this statement suggests, the CTSI was a first cousin to the Irish Vigilance Association and the wider social purity movement, all of whom saw great threats to Irish morals from popular culture, especially that imported from England.

Leaving aside the Bishop of Clonfert’s uncompromising address at its founding however, the Catholic Truth Society of Ireland generally left thundering condemnations of ‘evil literature’ to other branches of the social purity movement, and instead focused on producing and distributing its own publications. It focused on books (or more truthfully, pamphlets), perhaps realising that the production of weekly or even monthly periodicals was difficult to sustain and less likely to be successful in a market of fiercely competitive commercial penny papers. In its early years, the CTSI focused primarily upon non-fiction publications which mainly fell into two categories – the history of the Catholicism in Ireland, and the lives of saints. Examples included A Short History of some Dublin parishes (1905), St Frigidian: an Irish Saint in Italy by Michael O’Riordan (1902), The Church and the Working Classes by Peter Coffey (1906) and the intriguingly-titled The Manliness of St Paul by the Very Rev. Walter MacDonald. After the first few years of the Society’s existence, more contemporary topics of social and even political interest were addressed. These included Socialism by Rev. Robert Kane (1909), Marriage by Rev. John Charnock (1910) and The Management of Primary Schools in Ireland by Right Rev. Monsignor Hallinan (1911). It is noticeable that in its earliest years the CTSI published almost no fiction. This was despite its stated aim of competing with the ‘infidel and immoral publications’ flowing into Ireland, most of which focused on fiction – as has been discussed here on this blog before, short and serial fiction, along with cheap novels, were the dominant popular cultural form of the early 20thC, not yet having yielded their place to movies as the source of most people’s leisure entertainment. Instead, the Society’s initial output mirrored the non-fiction content of many popular journals and magazines, the informative articles about history and culture, in this case with a very strong Catholic inflection. And although they were longer than the short factual articles published by the Irish Packet or Ireland’s Own, they were still brief – pamphlets rather than books. For example, The Manliness of St Paul was only 27 pages, and The Management of Primary Schools in Ireland was 36 pages, both of these being typical lengths for CTSI pamphlets. This was probably motivated by a combination of factors – shorter publications could be cheaper (many CTSI pamphlets were only 1d), but in the era of short and disposable popular literature, this format may also have been more appealing to readers. Like other branches of the social purity movement in this era, the CTSI appear to have had a fairly clear grasp of the popular culture they were attempting to compete with (this, it might be argued, is one of the most important distinctions between the Church’s interactions with popular culture a century ago, and their efforts to make similar interventions in more recent years), and paid attention to their publications’ appeal to potential customers. As well as encouraging subscriptions, they also utilized the pre-existing network of Catholic churches and schools to display and sell their publications, even advertising and selling display cabinets for this purpose, from 15 shillings for a small set of wall shelves, up to 36 shillings for a freestanding cabinet which would display 18 pamphlets.

The Society did begin publishing fiction well before World War One, and this became a more and more important part of their output over the coming years and decades. Like their other publications, most of their fiction was short – one of their earliest stories for example was Avourneen by Rosa Mulholland (Lady Gilbert), published in 1905 and only 16 pages long. In effect, they were publishing in stand-alone, pamphlet form, the extended short stories which were so popular in weekly penny papers like Ireland’s Own. Indeed, many of the same authors wrote for the Irish popular press and the Catholic Truth Society, including Mulholland herself. By 1919, that inveterate cataloguer of Irish literature Stephen J Brown had commented in his exhaustive annotated bibliography Ireland in Fiction that the CTSI’s principal purpose ‘is religious and moral propaganda’, most of which were ‘distinctively Catholic in tone’, observations which from Browne, who was himself a Jesuit, were intended to be complimentary. He also gave an indication of the scale of the Society’s publications by that point, asserting that in the 20 years since its founding in 1899, it had already distributed more than 7 million copies of its publications.

Less well-known Irish writers seem to have been able to use the CTSI as a platform for their work too, suggesting that the Society may have had to actively seek out writers who would produce work of the kind they were looking to promote. One example of such authors was Patrick Ivers-Rigney, a National School teacher from Cork. Born in 1879, Ivers-Rigney contributed stories to several story papers before he was 30, including (in 1907) a murder-mystery serial called ‘The Mystery of a Railway Car’ for the Irish Emerald, which the paper tied to a competition inviting readers to guess the murderer and how they committed their crime. By 1915, he was also writing for Ireland’s Own, a complicated serial called ‘The Mystery of the Yellow Lough’ which featured an attempt at forced marriage, a contested legacy from America and the revelation of murder when the local lough is drained to reveal multiple skeletons. These stories were hardly the kind of ‘sound Catholic literature’ the CTSI had promised when they were established, but despite this (and perhaps because Ivers-Rigney also had a parallel career writing about education policy for Catholic journals), during the 1920s and 1930s they published 23 of his stories, including Circumstantial Evidence (1927), The Church Street Mystery (1930), The Mysterious Portmanteau (1931) and The Rahaniska Ruby (1931). Like most other CTSI fiction, these stories were all less than 30 pages long, and were extended short fiction very similar to the work he had published in story papers. Ivers-Rigney’s work, along with that of many others, suggests that as the decades went on the CTSI broadened their scope from ‘moral propaganda’, presumably in order to attract readers.

Indeed, the Society’s activities during the early years of the Free State appear to have become both more commercial and more wide-ranging, as they began to include the sale of vestments and religious artefacts as well as the sale of their publications, and by the mid-1920s they were also organising pilgrimages. This prompted the setting up of the Veritas Company as a commercial operation, run from the CTSI’s shop on Lower Abbey Street (and which is still open to this day). Probably inspired by the success of the 1932 Eucharistic Congress in Dublin (which saw visitors and press from all over the world and a mass for one million people in the Phoenix Park), their religious travel agency became a significant business during the early 1930s. In 1933 they organised a 10-day pilgrimage to Lourdes which consisted of 2,500 pilgrims (including several TDs and government ministers), accompanied by an officially-deployed detachment of the Irish Army to oversee the logistics of their movements and accommodation. Tickets for the pilgrimage cost £14 15s (with a discount for invalids), an enormous sum for most ordinary Irish people at that time.

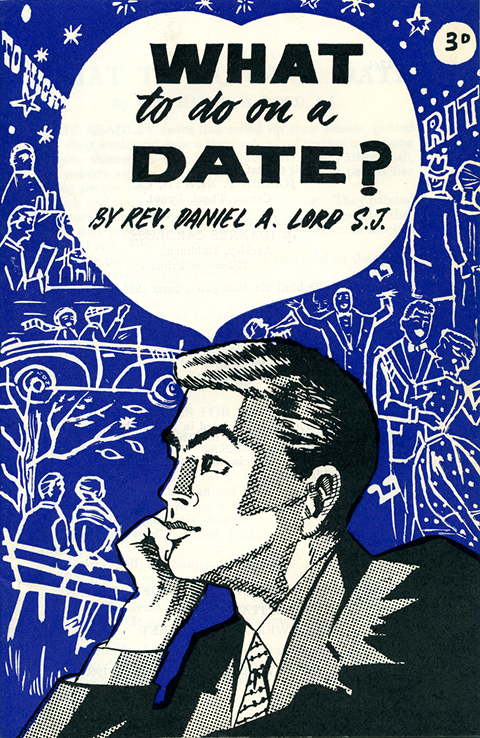

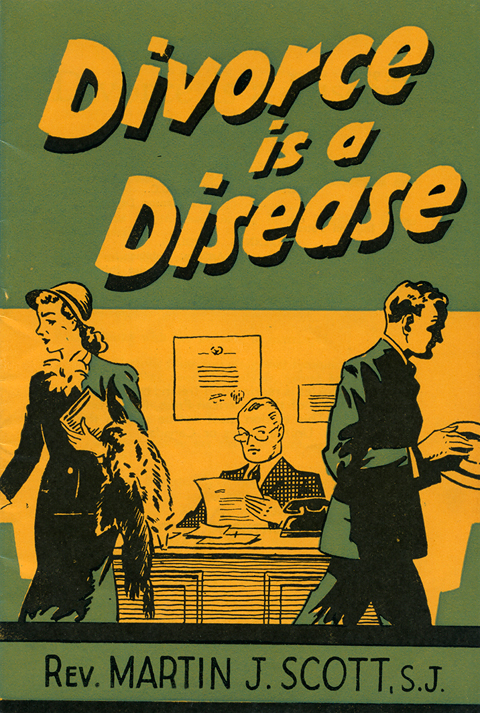

While the arranging of pilgrimages and selling of religious artefacts was overseen by the Veritas Company as a separate business, a keen business sense also seems clear in the CTSI’s publishing operations during the mid-20thC. For example during these decades they not only increased their output to include a wide range of fiction, as well as pamphlets on religious education, social issues and personal advice, but they also placed considerable emphasis upon the cover art of their pamphlets – which would also have helped their publications to compete in the crowded market of popular magazines and pulp fiction. Many of these covers (such as the ones shown here) were of very high quality, so much so that in 2013 some were reproduced as limited edition prints and collected into a book, Vintage Values, which is available here (and definitely recommended for anyone interested in graphic design).

In 1969, the Veritas Company effectively took over the Catholic Truth Society of Ireland, taking on all of its publishing activities. As the decades passed, they became less and less of a force within popular culture (despite having set up a broadcasting operation during the 1960s in a very explicit attempt to keep up with new media technologies). Nevertheless, as the only publishers of religious textbooks approved for use in Catholic-controlled primary schools, the legacy of the CTSI’s commitment to ‘sound Catholic literature’ continues, as does its strongly commercial purpose.

References

Stephen J Brown, Ireland in Fiction: A Guide to Irish Novels, Tales, Romances and Folklore (Dublin: Maunsel, 1919)

Lir Mac Cárthaigh, Vintage Values: Classic Pamphlet Cover Design from 20th Century Ireland (Dublin: Veritas Publications, 2013).

Interesting article. Kevin O’Higgins delivered a talk entitled The Catholic Layman in Public Life which was subsequently published by the society. Msgr Hallinan, mentioned in the piece, was parish priest of my hometown (Newcastle West, Co Limerick) and succeeded O’Dwyer as Bishop of Limerick. We have a few books at home signed Bishop Elect which were given to altar servers in the family at the time.

LikeLike

Hi Frank – thank you, I’m glad you enjoyed it. And I think that for many decades almost every home in Ireland must have had CTSI books and pamphlets – they were probably the most influential publishers in the country for a long time and that’s been almost completely forgotten!

LikeLike

Hello Catholic Truth Society

I see that my great Aunt Lady Rosa Mulholland Gilbert wrote when she was young AVORNEEN 28 page pamphlet and I believe you have a copy that I may see. If it is at all possible I would like to copy it as it may be free domain now. I could be wrong and I cannot for the life of me find it Anywhere! So I thought her publisher may have archived her story 1905 . Please and Thank you in advance it would help me to get a compendium of data of her life for mine.

Yours Sincerely

Mark Mulholland great grand before of Lady Gilbert

My Great Grandfather was William Mulholland her brother to all three Girls. My uncle, my father’s brother, was named William like His Honor William Mulholland Q.C. magistrate in the town around there from NEWRY? Anything would help .

Again Mark Mulholland

704 Kobe Court ,

Everson, Wa. 98247

markmulholland1953@gmail.com

LikeLike

hi Mark – I’ve sent you an email!

LikeLike

Hello Stephanie Rains I saw the text you sent with Catholic Truth z society that is daily sent out . Um thank you and I’m so glad you acknowledged my comment with what seems to be just that. My comment and daily C.T.S. articles. I’m not very savvy with email techy stuff but I’m missing yourt one as you mentioned but I’ll lo saormentioned reply. I’m not trying to be criptik… Lol but I didn’t get it? I know you sent it just couldn’t find it 😔. Mark Mulholland again markmulholland1953@gmail.com… Love in Christ MM

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so sorry I found your wonderful reply prompt and detailed like a Professor from Maynooth University would faithfully and bless your soul. I’m readin’ it new. Phonetic Irish inference. See what I did dare. SLANTYA. We’ll be visitn again. Soon . MM

LikeLiked by 1 person