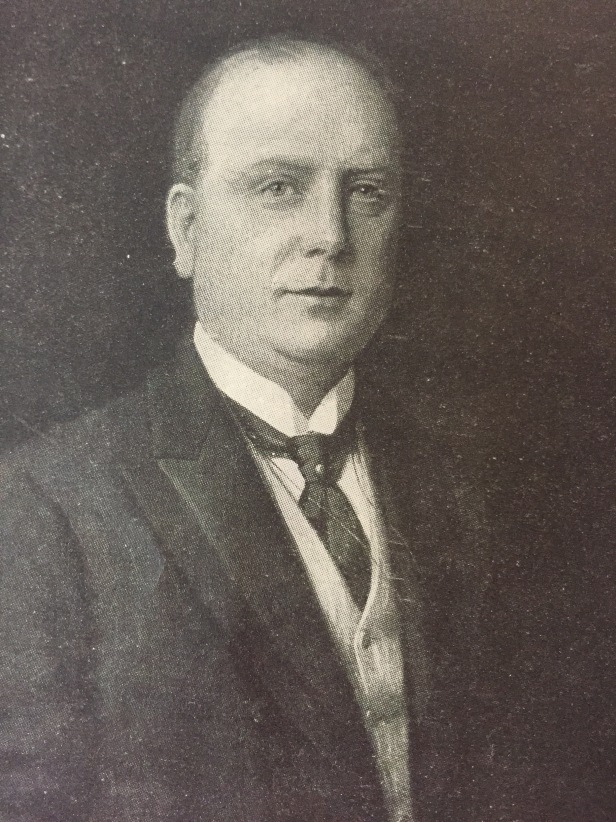

After the Christmas festivities of the last post, this one will begin the New Year in an appropriately dyspeptic fashion by focusing on Ramsay Colles. One of the oddest characters of Irish publishing in the early 20thC, Colles is now almost entirely forgotten except when it is (occasionally) recalled that in 1900 he was literally horsewhipped by Arthur Griffith in order to defend the honour of Maud Gonne. This was undoubtedly the most sensational moment of his career in journalism, but it wasn’t entirely out of character for a man who appears to have thrived on conflict.

Ramsay Colles was born in 1862 in Bodh Gaya in India, where his Anglo-Irish father was serving in the Indian Civil Service. However he was brought up in Ireland, and attended Wesley College in Dublin. In 1896 he married Annie Sweeny, who was also a journalist and editor, and who will be the subject of the next blog post here. They had one son, Edmund, in 1898 and lived for some years on Wilton Terrace in Dublin. Like a great many journalists of his generation (including Matthias McDonnell Bodkin, the editor of the Irish Packet) Colles combined journalism with the law, having qualified and practised as a barrister. It’s hard to determine exactly how wealthy Colles was – his background and some aspects of his life strongly imply a private income, but just how much is unknown, and both the length and variety of his career in journalism and publishing suggests that he may have needed to earn money to supplement his inherited wealth. His politics are a great deal easier to determine however – Colles was a hard-line Tory, who loathed every aspect of Liberalism, the Home Rule movement, the literary revival (and all figures associated with it), the Irish language, public libraries, Dublin Corporation, and most of modern life in general.

By 1896 he was working as a journalist for the Dublin Daily Express – and although he was already 34 by then, this may have been his first journalism work, because it was not until that year that he joined the Institute of Journalists, a London-based organisation founded in the 1880s as a forerunner to the National Union of Journalists, and which had many Irish members prior to Independence. Colles worked for the Express for just two years, however, before moving on to edit the Irish Figaro – a society and cultural review paper he had bought earlier in the decade and with which he and later his wife Annie would be associated for several years. The Figaro had begun in 1892 as Irish Life, changing its name after just one issue to the Dublin Figaro, before changing again to Irish Figaro in 1895. In 1901 it became the Figaro and Irish Gentlewoman for its remaining years (it appears to have ended sometime in or around 1904). If this seems a rather chaotic number of name changes for a publication which only lasted just over a decade, this was fairly in keeping with Colles’ general editorial tone and style, which was distinctly less than professional on occasion.

The Figaro was a weekly society paper costing one penny, which published theatre and musical reviews (Colles appears to have been a genuinely enthusiastic supporter of popular theatre and music in Dublin), reports on high society events and marriage announcements, and other occasional columns, for while including a women’s column called (appallingly) ‘Topicalities Femina’. It always contained numerous advertisements, typically for major food and household brands as well as a wide range of up-market Dublin businesses, such as department stores, restaurants and hotels. The Figaro has also been identified as the publisher of advertisements for the real Alexander Keyes, whose fictional advertisement designs Leopold Bloom is working on during the course of Ulysses. However, many of its 16 weekly pages were taken up with a long, wide-ranging and typically splenetic editorial column entitled ‘Entre Nous’ (Colles appears to have had a genius for awful column titles). These editorials were, throughout the paper’s existence, signed by ‘Sydney Brooks’. However it is most likely that this was a pseudonym, and that Colles not only wrote the editorials, but was widely understood to do so by the Figaro’s readers. Not only is the writing style very similar to that of his memoir, In Castle and Court House: Being Reminiscences of 30 Years in Ireland (1911), but more importantly he was frequently identified as being the Figaro’s editor in the various legal cases he was involved in.

The most sensational of these cases – and the only reason Colles’ name is ever remembered these days – were in the aftermath of Arthur Griffith bursting into the Figaro’s offices in 1900 and literally horsewhipping Colles in defence of Maud Gonne’s nationalist good name. The Figaro had just published an article claiming that Gonne was in receipt of a British Army pension inherited from her father, and was therefore a hypocrite for being actively involved in opposing a British Army recruitment campaign for Irishmen to fight in the Boer War. Rather disappointingly, Griffith only appears to have inflicted damage to Colles hat (and presumably his dignity), but he was nevertheless prosecuted for assault (a charge he did not contest), fined one pound and bound over to keep the peace. Immediately after this however, Maud Gonne sued the Figaro for libel, a case which Colles settled (by issuing a formal apology to Gonne) some way into a trial which was being gleefully reported by the press. Both protagonists returned to this incident in their later memoirs. For his part, Colles claimed that he had evidence to prove the truth of his story about Gonne’s military pension, but did not produce it because his source had been the John Mallon, the Assistant Commissioner of Police, and to have revealed this in court would have been too politically-sensitive – although he did not explain why, only a decade later, he now felt free to share this information in his memoir. Even more remarkably, he also claimed that Gonne had only sued him at all because she was suspected by Michael Davitt of being a British double-agent and (it was implied) may therefore have been in fear for her own safety. Gonne, on the other hand, claimed in her 1938 memoir A Servant of the Queen: Reminiscences, that not only was the Figaro ‘…a little rag….subsidised by Dublin Castle’ but also that Colles’ barrister had later admitted to her that his legal costs in the libel case were paid by the Castle (in his own memoir, Colles ambiguously describes them as having been met by a subscription list contributed to by ‘friends’). Gonne provides no evidence for her claim about the Figaro’s subsidy from the Castle (and it is made well after Colles’ own death), so it is impossible to determine its accuracy. To put it mildly, neither Colles nor Gonne was a trustworthy source about the other, but Gonne’s allegation is certainly not impossible to believe – and it would help to explain how the Figaro could afford to publish a weekly paper on good quality paper and with frequent photographs for only a penny, when the other penny weeklies (such as the Irish Packet) were published using the very cheapest paper with few illustrations and certainly no photographs.

Throughout the 1900 libel trial however, Colles was consistently identified in court as being both the proprietor and editor of the Figaro, meaning that the regularly apoplectic six-page editorials produced on a weekly basis were his own work. These ranged widely in topic, apparently governed purely by Colles’ grievances of the week, and only leavened by regular theatrical and musical reviews of performances taking place at the Gaiety or Queen’s theatres. Each instalment of ‘Entre Nous’ was headed by the rather aggressive statement that ‘Any of my readers who disagree with any statements which appear in Irish Figaro are invited to correspond with the Editor’. Colles’ own disagreements with daily life in Ireland ranged far and wide. The key figures of the Literary Revival and the Abbey Theatre (especially WB Yeats and George Moore, who he once called ‘puff-created mushroom men’) were the individuals most frequently attacked – sometimes it has to be admitted with a certain degree of comic effect. He described Yeats as ‘an utter literary fraud’ whose work had ‘an utter lack of sense’, and once quoted the music critic John F Runciman’s assessment of Yeats’ distinctive system of ‘singing’ poetry, ‘Having superfluously stated that he [Yeats] knew nothing of music, he proceeded to reveal his new musical art…and I have scarcely yet recovered from my extreme surprise’. On another occasion a Figaro editorial expressed regret at the news that George Moore was not learning Irish (an enterprise Colles generally disapproved of) because ‘readers would be much benefitted if Mr Moore betook himself to learning Irish and wrote in future exclusively in that language and ceased to sully the English tongue with his filthy tales’. If figures such as Yeats and Moore were frequently the subject of derogatory remarks in Figaro editorials, Colles’ expressed views on broader social issues could be even more aggressive. In 1900 he felt that the Poor Law Guardians in Dublin were being far too generous to the city’s poor, commenting nostalgically that ‘The old idea was merely to give shelter and food to the destitute, and neither in too pleasant a form, in order not to encourage idleness’. He was predictably opposed as well to the Land Acts, arguing that, ‘Leaving aside the very great doubt whether your peasant-proprietor, when you have got him, could be made a flourishing and contented citizen, purchase means the exodus of the upper class from the country’.

Colles was an active member of the Freemasons in Dublin, and in 1900 he established a periodical specifically for the organisation in Ireland, called Irish Masonry Illustrated. It isn’t clear how long this ran – only a couple of years’ worth of issues are extant in the National Library of Ireland, and it may well only have been in publication for a short time. Colles mentions the magazine with some pride in his memoir, but does not indicate how many issues were published. In what may have been a unique combination of interests, he mixed his enthusiasm for Freemasonry with an interest in Buddhism – according to his memoir this was inspired by knowing he had been born at one of its most important shrines in India, and it led to his becoming the official Irish representative of the Maha-Bodhi Society in Ireland in 1901 (and indeed he is listed as such in Thom’s Directory for several years).

In January 1901 he formally transferred the editorship (and possibly ownership) of the Figaro over to his wife Annie, who continued to publish it until it ceased publication sometime around 1904, by which time Ramsay Colles himself was living in London, where he appears to have remained until his death in 1919. In fact one interpretation of the information available about his life and career after 1901 is that he and Annie may have been unofficially separated, because she remained in Dublin until after his death, and there is no indication that they lived together after 1904 at the latest. In the 1911 Irish census, for example, his name does not appear at the family home in Morehampton Terrace and Annie Colles is described as being the ‘head of household’. This is a speculative interpretation, but such arrangements were not unusual as a solution to marital breakdown (especially for people of their social class, who had the resources to live separately) and it would explain why they do not appear to have lived together for the final 15 years of Colles’ life.

After his move to London, Colles continued to work as a periodical editor (and proprietor) for a number of years. Given his rather splenetic editorial tone, it is slightly surprising that he appears to have specialised in editing women’s magazines. In 1904 he founded and ran Chic: A high-class ladies’ illustrated paper, (which was wound up owing its printers money) and then from 1905-1910 he edited another London women’s magazine called Madame, which described itself in a publishing trade journal as ‘an illustrated magazine, devoted to the interests of women, containing articles, stories and social news’. He also published several literary and historical books during his later years – editing both The Poems of Thomas Lovell Beddoes in 1907 and The Complete Poetical Works of George Darley in 1908, before publishing The History of Ulster from Earliest Times to the Present Day in 1919, the year of his death.

Colles was only 57 when he died in London in February 1919. He received brief obituaries in the Freeman’s Journal and the Irish Independent, but in both cases this was largely in order to recall his confrontation with Arthur Griffith and court case against Maud Gonne. He was only ever a minor figure in Irish journalism, if undoubtedly a colourful one. A century later, he remains difficult to fully understand – a belligerent Tory and Freemason, fulminating against perceived liberal outrages as varied as Home Rule, the Irish language and public libraries, he was also fascinated by Buddhism and spent much of his career writing and editing ladies’ magazines. And despite the likelihood that he and his wife lived separately for much of their marriage, he does seem to have been actively supportive of her journalism career, a surprise in itself from someone of his deeply conservative social and political views. Her career was also varied and sometimes colourful, and needs its own post, which will appear here very shortly.

References

Ramsay Colles, In Castle and Court House: Being Reminiscences of 30 Years in Ireland (London: T Werner Laurie, 1911).

Maud Gonne, A Servant of the Queen: Reminiscences (London: Gollancnz, 1938).

Mary Power, ‘Without Crossed Keys: Alexander Keyes’s Advertisement and The Irish Figaro’, James Joyce Quarterly, Vol. 32, No. 3/ 4, 1995, pp. 701-706.

Thank you Stephanie for such an in-depth insight into both of these beautiful people. Ramsay is my 3rd Great Uncle so I like to read anything on his life whenever I can. Your research into Ramsay (Richard William Colles) was really well researched and has given me some new avenues to explore. Thank you for revealing a picture of Annie Sweeney for me. I have a lot of powerful women in my family and it is awesome to see the face of another fighter born way before her time.

LikeLike

Hi Lorin, I’m very glad to hear that you found the blog posts useful! The aspect of Ramsay Colles’ career I’d like to know more of is the London papers he edited after he left Ireland, so if you find anything about those I’d be very grateful to hear about it!

LikeLike

Stephanie, I found a book by Ramsay Colles, there is a note in the cover to W.P. Ryan, signed by Ramsay Colles. I can give you the quote but would like more of the history first if you would be so kind.

My grandfather was a doctor in Sligo. Another of his patients was Yates.

My beautiful father refused to tell me his history the only quote i remember: ‘the school of hard knocks.’ He was sent to boarding school at age 7.

He was born in Sligo in 1928, July 1st. David Norman Gerard Swan.

Sadly my grandfather shot himself. But as history does little to reveal, I have naught but my memories of my silent father and his quietude of his life.

I found this book ‘In Castle And Court House: Being Reminisceences of 30 Years in Ireland’

It really is one of the first lights into my generic past and, when carefully read I would like to pass this delicious book on to those who know and care to follow.

I hope this is of interest to you.

I am now 56 and have only just fallen for Hemminway!

Louisa J Swan.

LikeLike

Hi Louisa

thanks for getting in touch and that’s really interesting that your grandfather’s copy of In Castle and Courthouse was signed by Colles. There would have been no such thing as official book signings by authors in those days, so it must mean they knew each other in some way, or had friends in common. That friend definitely wouldn’t have been Yeats because Colles loathed him, he often attacked him in his editorials! But they would both have been part of a relatively small social class of wealthy (and Protestant) families so perhaps your grandfather was connected to that group as well. The book itself is very typical of memoirs of that era – really fascinating but also very guarded with almost no personal information of the kind people include now. I’m glad you like it though!

LikeLike

Very interesting read; From my research into First World War soldier-drawn cartoons, I believe he may have been on the staff of the Soldier’s newspaper Blighty.

LikeLiked by 1 person